I'm hoping to get in my Christmas mystery review and two other books this coming week, but in the meantime I thought I would review my first full year on the blog.

The biggest news was the appearance in June of my book, ten years in the making,

Masters of the "Humdrum" Mystery: Cecil John Charles Street, Freeman Wills Crofts, Alfred Walter Stewart and the British Detective Novel, 1920 to 1961. With it, I hope to persuade modern mystery critics and fans that the Golden Age of the detective novel (roughly 1920 to 1940) was a more diverse period, ideologically and aesthetically, than is admitted and also that these specific authors had their merits (some critics and fans know this already, of course, but many don't).

The book has received some excellent notices, such as Jon L. Breen's in

Mystery Scene, J. Kingston Pierce's at

Kirkus Reviews and Geoff Bradley's in

CADS. Also a great piece by Patrick Ohl on his blog,

At the Scene of the Crime.

I also contributed introductions to Coachwhip's new editions of titles by J. J. Connington and Todd Downing. My own book on Todd Downing will be out, after a delay, in January (you'll be hearing more about this one).

All these books are available from Amazon. Additionally, titles by Connington are being reissued in Ebook format by Orion's Murder Room. I hope they can follow suit with John Street and Freeman Wills Crofts. Those who control Street's literary estate have not been notably helpful to date.

Now to the books discussed this year on the blog!

Herewith is the list of the them, by year of publication:

Great Porter Square (1885), by Benjamin Farjeon

The Confession (1917), Mary Roberts Rinehart

Carteret's Cure (1926), Richard Keverne

The Copper Bottle (1929), E. J. Millward

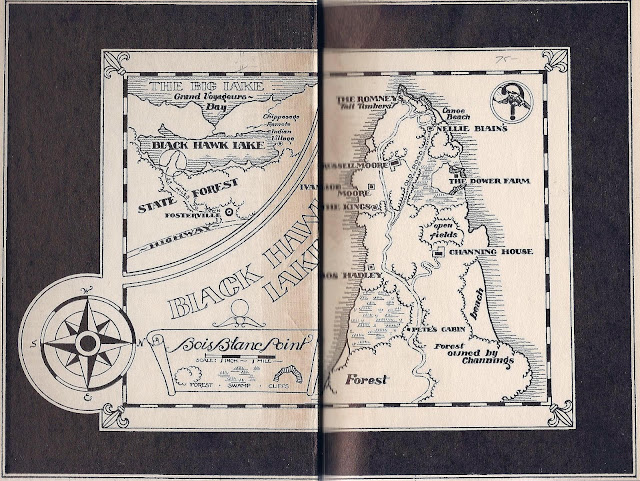

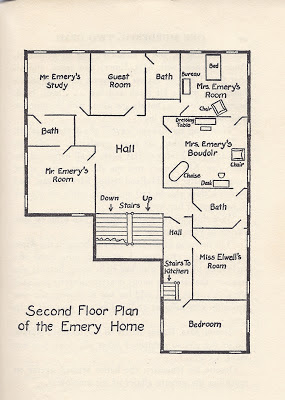

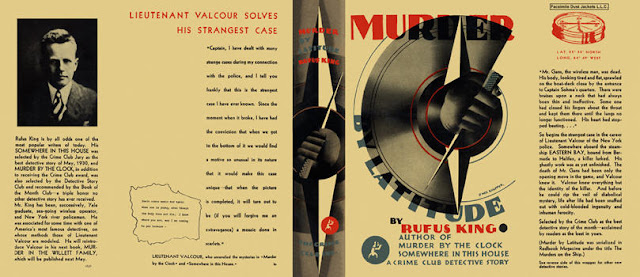

Murder by Latitude (1930), Rufus King

Castle Skull (1931), John Dickson Carr

The Floating Admiral (1931), Various Authors

Maigret in Holland (1931), Georges Simenon

The Matilda Hunter Murder (1931), Harry Stephen Keeler

Six Dead Men (1931), Stanislas-Andree Steeman

The Thirteenth Floor (1931), J. F. W. Hannay

Murder on the Yacht (1932), Rufus King

Red Warning (1933), Virgil Markham

The Warrielaw Jewel (1933), Winifred Peck

Cartwright is Dead, Sir! (1934), Hugh Baker

Death of a Banker (1934), Anthony Wynne

A Girl Died Laughing (1934), Viola Paradise

Desire to Kill (1934), Alice Campbell

Give Me Death (1934), Isabel Briggs Myers

Insoluble (1934), Francis Everton

The Lesser Antilles Case (1934), Rufus King

Still Dead (1934), Ronald Knox

Crime in Corn Weather (1935), Mary Meigs Atwater

The First Time He Died (1935), Ethel Lina White

Halfway House (1935), Ellery Queen

How Strange a Thing (1935), Dorothy Bennett

Murder with Pictures (1935), George Harmon Coxe

Smoke Screen (1935), Christopher Hale

Vultures in the Sky (1935), Todd Downing

A Frame for Murder, Kirke Mechem (1936)

Murder of a Matriarch (1936), Hugh Austin

Death for Dear Clara (1937), Q. Patrick

Invitation to Kill (1937), Gardner Low

Murder a la Richelieu (1937), Anita Blackmon

The Third Eye (1937), Ethel Lina White

Todmanhawe Grange (1937), J. S. Fletcher

Banbury Bog (1938), Phoebe Atwood Taylor

The Bloody Tower (1938), John Rhode

Double Death (1939), Various Authors

Murder in Stained Glass (1939), Margaret Armstrong

The Affair in Death Valley (1940), Clifford Knight

Maigret and the Spinster (1942), Georges Simenon

The Scarlet Circle (1943), Jonathan Stagge

Absent in the Spring (1944), Agatha Christie (as Mary Westmacott)

The Vultures Gather (1945), Anne Hocking

Death in the Night Watches (1945), George Bellairs

Museum Piece No. 13 (1946), Rufus King

Death Before Wicket (1946), Nancy Spain

Poison for Teacher (1949), Nancy Spain

Knight's Gambit (1949), William Faulkner

The Arm of Mrs Egan (1952), William Fryer Harvey

Death in the Fifth Position (1952), Gore Vidal (as Edgar Box)

Venom House (1952), Arthur Upfield

Death Before Bedtime (1953), Gore Vidal (as Edgar Box)

Death Likes It Hot (1954), Gore Vidal (as Edgar Box)

Man Missing (1954), Mignon Eberhart

The Barbarous Coast (1956), Ross Macdonald

Licensed for Murder (1957), John Rhode

The Ferguson Affair (1960), Ross Macdonald

The Turret Room (1965), Charlotte Armstrong

The Protege (1970), Charlotte Armstrong

The Victorian Album (1973), Evelyn Berckman

The Black Tower (1975), P. D. James

The Blackheath Poisonings (1978), Julian Symons

Waxwork (1978), by Peter Lovesey

Nightshades (1984), Bill Pronzini

The Wench is Dead (1989), Colin Dexter

Going Wrong (1990), Ruth Rendell

Asta's Book (1993), Ruth Rendell (as Barbara Vine)

Dover: The Collected Short Stories (1995), Joyce Porter

More Things Impossible (2006), Edward D. Hoch

A Mammoth Murder (2006), Bill Crider

Not in the Flesh (2007), Ruth Rendell

73 books! This is not counting four capsule John Dickson Carr reviews I reprinted here.

|

| Will Ruth Rendell seize the crown next year? |

Only four volumes of short stories, by William Faulkner, William Fryer Harvey, Joyce Porter and Edward D. Hoch, but I also did a piece on Edith Wharton's superb "A Bottle of Perrier" and one comparing the short stories of Bill Pronzini and Dashiell Hammett. There is also an oddity, a lyrical murder mystery poem by Dorothy Bennett.

Most reviewed author: Rufus King, who died forty-six years ago. Runner-up: Ruth Rendell, very much with us still.

So that's 68 novels, 35 of them from the 1930s. I guess it won't surprise you to learn that I think the formal detective novel achieved a state of perfection in the thirties that has never since been bettered.

I did mean to review more recent books, and will try to do better next year. But there are so many blogs devoted to the newer stuff already. I think interesting things are being done today, to be sure, but my focus will continue to remain on older works.

I also reviewed an interesting book on Ellery Queen, Joseph Goodrich's

Blood Relations: The Selected Letters of Ellery Queen, 1947-1950, Michael Dirda's winsome and Edgar-winning

On Conan Doyle: Or, The Whole Art of Storytelling and Jon L. Breen's fine collection of genre essays,

A Shot Rang Out.

Lately I admittedly have been reviewing a preponderance of novels by American authors, but I have become fascinated with the sheer volume of classical detection produced by Americans.

The notion that the genre in the United States was dominated during the Golden Age by hard-boiled writers could not be more wrong, it seems to me. Aside from the so-called HIBK school of Mary Roberts Rinehart and Mignon Eberhart and other women writers (which is getting a little attention from academics now), there were numerous male writers in the classical tradition, like S. S. Van Dine, Ellery Queen, Rex Stout and Rufus King.

As critic Jon L. Breen has pointed out, Queen gets shockingly little attention today (the same is true of Stout, which is especially strange when one considers that the Nero Wolfe novels have remained in print--there is really no excuse for the critical neglect here).

Anyway, with 66 novels blogged in 2012, I think I will do a top ten (or or twenty) for New Year's. What will the

Best Blogged Books of 2012 be??? Your Passing Tramp will have to do some heavy cogitation....

.jpg)