Ir would perhaps not be too much to say that it was the most horrible house in the United States of America, at least in so perfect a state of preservation. In shabby sections of little towns you can sometimes find the tottering remains of the monstrosities of 1876, but on the Peckham house the paint was shiny new. A fine shade of mustard-and-water brought out its every feature: the central Gothic spire, flanked by four balconies, the overhanging peaks of the second-story windows like little Swiss chalets, and the miles of jig-saw carvings that enlaced porches, piazzas and porte-cochere. From the street a walk of bulging bricks led up between a weeping willow and a cedar of Lebanon. On the right the lawn showed a patch of pale green whence an iron stag had been tardily removed.

On closer view the house was worse. There was a mad quality about it. Under second-story gables, doors opened out onto space. The jig-saw patterns were insane. It smelled of owls in the attic and suicides in the cellar. It was not a house you would want to meet on a lonely road at midnight. It was hag-ridden.

On this sunny April afternoon the door opened and the hag stepped out....

From No Bones About It, by Ruth Sawtell Wallis

One of the considerable number of American intellectuals who enjoyed reading mysteries during the Golden Age of detective fiction, Ruth Sawtell Wallis (1895-1978) in her late forties finally decided herself to dabble in the fine art of fictional murder (more on her life on the way).

Between 1943 and 1950 Wallis published five well-received detective novels, beginning with the prizewinning Too Many Bones, reviewed by blogger John Norris here. The next year came another accomplished crime tale from her pen (or typewriter): No Bones About It.

This title suggests that Wallis (or her publisher, Dodd, Mead) had a "bones" series in mind, but in fact none of her remaining mysteries used the "b-word," if you will, in the title--which is just as well, because the title of No Bones About It is pretty meaningless anyway. (William F. Deeck's 1990 reviews of Wallis's first two novels have been reprinted here at the excellent Mystery*File site.)

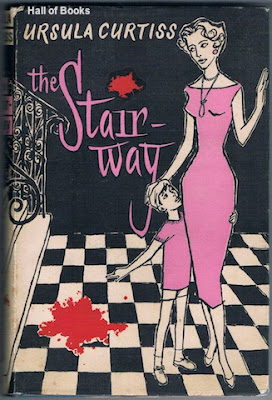

The jacket to the hardcover edition of No Bones About It is by an H. Koerner, who also designed the jackets around this time for Agatha Christie's Towards Zero and John Stephen Strange's Look Your Last, but I don't know who H. Koerner was, unfortunately. I do know s/he was not W. H. D. (Wilhelm Heinrich Detlev) Korner, the noted Westerns illustrator, because Korner died in 1938, before any of these mentioned mysteries were even conceived, let alone published (also the surname spelling is different, the "o" in the latter man's name carrying an umlaut, which I haven't produced here).

Whoever H. Koerner may have been, his Bones cover is a superbly creepy jacket design, looking for all the world beyond like something out of Charles Addams.

|

| they're creepy and they're kooky mysterious and spooky |

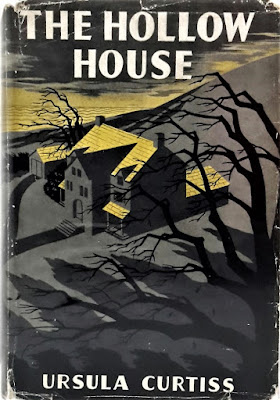

Of course what imaginative kid walking by a sprawling Victorian house, with queer turrets and jumbled jigsaw porches popping out all over, doesn't have a thrilling frisson of fear immediately and think "haunted house"? You always expect to see someone (or something) peeping out at you from behind a window, or perhaps a hand clutching at a curtain.

In mystery fiction there was a whole subgenre of spooky "old dark house" mysteries that, drawing on age-old Gothic tropes, took full advantage of such sinister settings. They went hand-in-hand with a slew of old dark house mystery films in the silent and then the talkie eras that lasted well into the 1940s. (See, for example, my review last Halloween of Abbot and Costello's Hold That Ghost, 1942).

In mystery fiction there was a whole subgenre of spooky "old dark house" mysteries that, drawing on age-old Gothic tropes, took full advantage of such sinister settings. They went hand-in-hand with a slew of old dark house mystery films in the silent and then the talkie eras that lasted well into the 1940s. (See, for example, my review last Halloween of Abbot and Costello's Hold That Ghost, 1942).American "Atmosphere Mystery" Queens Mary Roberts Rinehart--who authored, among other mysteries, The Circular Staircase, translated to stage and film as the influential old dark house film The Bat--and Mignon Eberhart specialized in menacing old dark house settings; and they had a host of female followers, many of whom were dismissed by male critics of the time as cornily foreboding HIBK (Had-I-But-Known) authors. But they were very popular and they remain so today among vintage mystery fans.

|

| Massachusetts design at the 1876 Centennial Exposition |

Good sketching of people and houses, well-integrated and suspenseful narrative, fine period flavor of 1932, and not a single Had-I-But-Known make this a leading entry in the atmosphere-romance stakes.

I share Boucher's opinion. Bones is an excellent mystery, successfully drawing on on one of the hoariest yet most perennially appealing themes in vintage mystery: the awful old relative who dominates her family to malign effect. Here the nastily-disposed oldster is the wealthy widow Mrs. Mattie Peckham, the "hag" in the quotation that heads this review. She's marvelously described by Wallis:

Mattie Peckham did not really look like a walking corpse. It was not that her face was so old, but that her teeth and her hair were so new. Too white, too back, and far too abundant. Under the inky puffs and pompadours her skin was shriveled and yellow, and the lips around the sparkling denture she wore were purple and wide. But seventy years of peering into other people's business had not worn out the small, bright black eyes.

Malevolent Mattie knows too much about people, and after taunting her relatives--her lately-returned "cousin" from Minneapolis, Minnesota, pretty and progressive-minded young career gal Janet Carter; her brother, Virgil West; and Virgil's family, consisting of Charlotte, his wife; Duncan, his son, lately returned from a dozen expat years in Paris; Louise, his dull daughter; and her fishing enthusiast husband, Ralph--with her dangerous knowledge, she ends up quite dead indeed, snuffed out in her bedroom by fumes from a can of the prophetically named stain remover OUT.

There's also a Polish (or Polack, as many of the narrow-minded locals put it) family, the Balutas, whose fortunes seem to be tied up with those of the old-money Peckhams, Carters and Wests. And then there's Mattie Peckham's Irish maid and all-round yes-woman, Bridie; the uppish West chauffeur, Jerry; and an enigmatic visiting Hollywood film star, Miss Mary Alden.

Before this suspenseful and well-plotted novel is over, there will be another death, rather graphically committed with a wicked knife everyone calls a snick-a-snee (also known as a snickersnee--see here for a blogger's visit to Ye Olde Snickernsee Shoppe), as well as two more attempted slayings. There's also that tragic fatal affair that took place on Christmas Eve 1920, poignantly detailed by Wallis in a prologue.

Eric Lund, an appealing investigator of Scandinavian heritage, debuts in this novel and would appear in two more Wallis tales. He's a nicely-drawn character, as are the others in No Bones About It. Wallis was a natural novelist and it is a matter of regret to me that she left the field of detective fiction after producing only five mysteries. No Bones About It is highly recommended--especially, as one reaches the startling denouement--for reading in lonely old houses on dark and stormy nights.

Happy Halloween!