Few people may appreciate today that in the 1920s--until the advent, in the middle of the decade, of Earl Derr Biggers and S. S. Van Dine--Carolyn Wells was, along with Englishman J. S. Fletcher, about the biggest thing in mystery novels in the US. Admittedly Wells and Fletcher were thrown in the shade somewhat by the rise not only of Van Dine and Biggers, but of Christie, Sayers, Crofts and all the rest of the classic British crew, not to mention Dashiell Hammett and the rest of the American tough squad. Yet with the rise of internet reprints, Wells, like Fletcher, is again being read and enjoyed by a perhaps surprisingly large number of people, considering that these are authors who seem to define the term "dated." In other words, they were old-fashioned even in the 1920s, but perhaps that is part of their charm today. (Incidentally, there's also an essay in Mysteries Unlocked by J. S. Fletcher.)

Reflective of her age (she was three years younger than Arthur Conan Doyle), Carolyn Wells grew up with, and loved, the word games found in the nonsense writing of authors like Edward Lear (1812-1888), Lewis Carroll (1832-1898) and her "literary chum" Gelett Burgess (1866-1951). The latter man was the American creator of the noxious Goops ("The Goops, they lick their fingers/and the Goops, they lick their knives/They spill their broth on the tablecloth/Oh! they lead disgusting lives!") and author of "The Purple Cow" ("I never saw a purple cow/I never hope to see one/But I can tell you, anyhow/I'd rather see than be one!").

Beginning in the 1890s, Carolyn Wells herself began emulating her idols, publishing verse in Punch and The Lark. She continued to emulate those idols in her original published and punning book of nonsense verse, Idle Idylls, was published in 1900 and her Nonsense Anthology, still in print today, first appeared two years later.

Yet around this time Wells discovered the mystery fiction of Anna Katharine Green (who also influenced Christie), and she was instantly won over to this addictive field of entertainment literature. (She also wrote a great deal of children's fiction in the first two decades of the 20th century, particularly tales, nearly two dozen in all, of the adventures of two jolly girls named Marjorie and Patty.)

In 1902, Wells penned the whimsical "A Ballade of Detection," detailing her love for the works of Green, Poe, Gaboriau, Du Boisgobey, Ottolengui and Conan Doyle, and in 1906 and 1907 there appeared, in serial form, her first detective tales, The Maxwell Mystery and A Chain of Evidence (published as novels in, respectively, 1913 and 1912). Her first detective novel, The Clue, was published by her lifelong mystery publisher Lippincott in 1909. The Gold Bag came the next year and her next original detective novel was Anybody but Anne in 1914. All these tales had her most frequently appearing sleuth, patrician detective Fleming Stone.

From that point on Wells published two, sometimes three, detective novels a year until her death in 1942. For the rest of the century, however, not a single mystery title by Wells was reprinted, as far as I can tell, barring a couple, one in England and the other in France--a remarkable literary extinction which makes her recent revival even more remarkable. (It should be mentioned here that she also wrote a notable text on mystery writing, The Technique of the Mystery Story.)

Wells certainly has had her critics over the years, and I started out my writing about her in a pretty critical frame of mind. But she has had her defenders too, like Mike Grost and the academic writer Stephen Knight; and over the years I've come to be more more judicious in my assessments of her writing.

I think Wells's earlier books are pretty weak, on the whole, though there are some appealing aspects even in the initial tales. (The Clue has a male-female amateur sleuth duo who to me are reminiscent of Christie's Tommy and Tuppence, anticipating that flippant flapper and her beau by a dozen years.) But beginning with The Curved Blades (1916) I think Wells' Fleming Stone series picks up several notches. (At his Pretty Sinister blog John Norris has written about Wells's Pennington Wise and Zizi tales, her second most important series.)

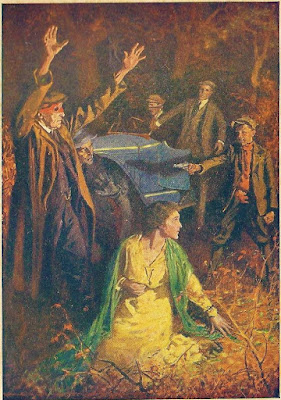

|

| Fibsy to the rescue (after Iris gets kidnapped yet again) frontispiece to The Diamond Pin |

Fibsy Maguire appeared with Stone in a total of eight mysteries between 1917 and 1923, including, right in the middle, The Diamond Pin (1919). Though there are some duds in the lot (see Feathers Left Around, 1923), on the whole I find this an enjoyable series. The Diamond Pin is no Vicky Van, for its part, but it's an entertaining little tale of more modestly scaled ambition.

The Diamond Pin has a setting which will be familiar to readers of Carolyn Wells mysteries: A little country town (Berrien), isolated and tranquil in spite of being located less than fifteen miles from New York. I thought Wells might have had in mind Meriden, Connecticut, but that's farther away and also had a population of about 30,000 in 1920, which to my mind is not so small. (There's also a Berrien's Island, near Rikers, in New York.)

In any event, the setting is typical of of Wells' own home town of Rahway, New Jersey (pop. about 11,000 in 1920), where Wells grew up with a sister and brother in privileged circumstances. Like suburban Connecticut and the Berkshires of Massachusetts, small-town, affluent New Jersey is a frequent Wellesian setting.

In The Diamond Pin there also is another common Wellesian feature: a fine country home, where a soon-to-violently-expire millionaire holds court over her/his restive dependent relations. Here we have Ursula Pell's house Pellbrook, where dwells the eccentric "old lady" (she's all of 62) and her lovely niece (there are no plain nieces in Wells books), Iris Clyde. The house is less fancy than some Wells domiciles (she generally prefers what was then termed monumental "colonial"--i.e., classical--architecture), but it's still rather a nice pad, with lots of rooms and a homey wraparound porch. Plenty of places to get murdered in, have no fear!

Aunt Ursula's distinguishing characteristic is her penchant--almost pathological I would say--for playing practical jokes on her dependents, be they servants or family relations hoping to inherit something from her in her will, which is in a constant state of flux.

Granted this is a familiar character type in mystery fiction (a later example I recall is an irritating jokester minister in Leo Bruce's Death on Allhallowe'en); yet Wells does Aunt Ursula, well, um, well, this being a character who was, I suspect, rather close to her own quaintly humorous heart.

|

| What is the secret of the diamond pin? 1920s Art Deco Cartier emerald, diamond and platinum pin brooch |

The local police--none too bright, these guys, but not so bumptious as in some Wells tales--have no clue as to how the murderer could have gotten out of the locked room, but they end up arresting for the crime Iris Clyde's charming but indebted cousin, Winston Bannard, who with Iris is the major beneficiary in Aunt Ursula's will.

The focus in the novel then turns, rather entertainingly in my eyes, to the matter of Iris's special legacy from her aunt: a diamond pin, which turns out actually to be, well--you really should read and see for yourself.

I will tell you that it transpires that the "diamond pin" must be a clue to the location of Aunt Ursula's fabulous collection of jewels (worth millions--Aunt Ursula's late millionaire hubby didn't trust the stock market, don't you know). Sinister strangers keep showing up at the Pell domicile, all of them in pursuit of that dratted pin. Like so many Twenties mystery thriller heroines, Iris manages to get kidnapped twice in the tale (once while coming to the aid of her pet dog, Pom-pom, whom we had never even heard a whisper of earlier--but don't laugh, PD James uses the same ploy, more or less, in two of her books to my recollection, except in those cases its a beloved pet cat--I take it PD James was a cat person).

|

| Throw it over my head? What on earth for, my dear? see alexanderpalace.org |

This is a fun, if modest, little mystery story, one even the jaded Wells critic should enjoy. You even get a wailing cook who throws her apron up over her head to express her dismay. This odd practice, familiar to me from other older mysteries, was amusingly noted by the late Marian Babson in one of her own mysteries. (Marian Babson knew this genre well.)

I'll have to get to that one someday! Meanwhile, some more on Wells coming this week.

Previous Carolyn Wells reviews at The Passing Tramp:

The Clue (1909) and The Curved Blades (1916)

The Mark of Cain (1917)

Raspberry Jam (1920)

Excited to hear Wells will be getting a reprint - Murder in the Bookshop, does sound a very tempting title. Didn't have the strongest of starts to Wells so it has been helpful to see which of her books are stronger.

ReplyDeleteI'm hoping for a nice edition of Vicky Van, being a Van 'shipper!

Delete